24 Sep 2019

When rowing fever was ignited by Harvard racing Oxford

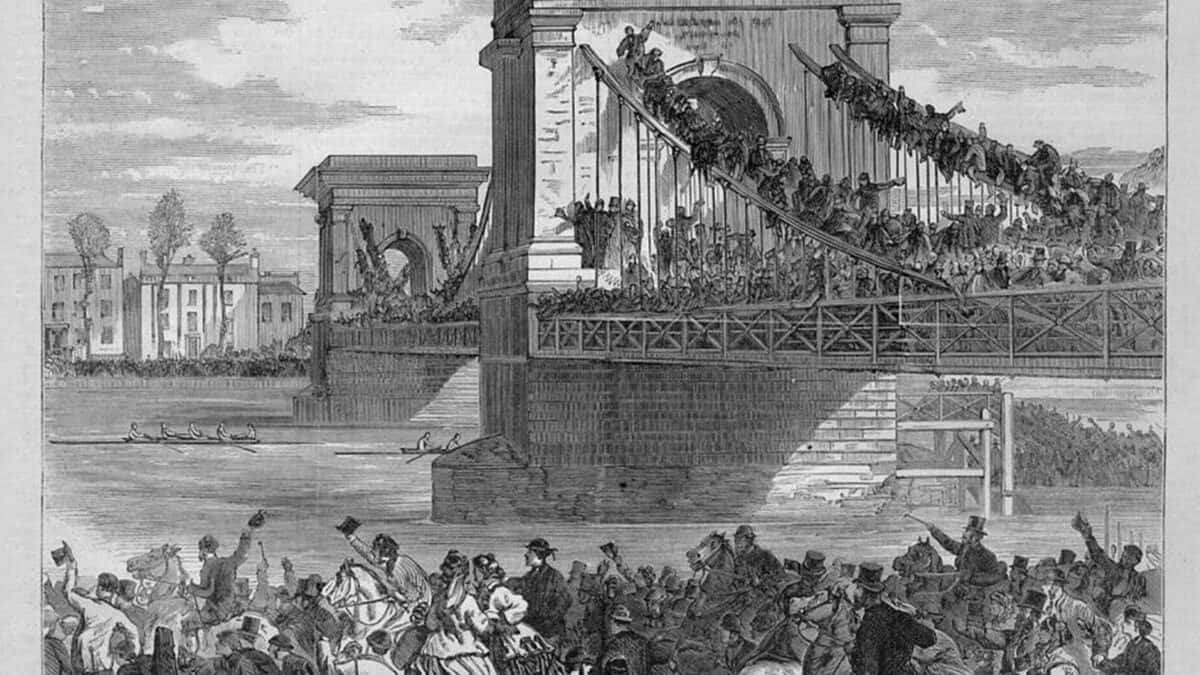

Half a million spectators lined the banks and bridges of Great Britain’s River Thames for the race between Harvard University (USA) and the British University of Oxford. It was a blockbuster event like nothing before in modern sport. The newly laid trans-Atlantic telegraph cable allowed for near instantaneous reporting across the ocean so that American supporters could follow the race. This enhanced the rowing fever that was sweeping across the United States and helped lay the foundation for American collegiate rowing as we now know it.

World Rowing spoke with former US Olympic rower and rowing historian Bill Miller to discuss the race’s legacy and why it still matters for rowers today.

The challenge

Emerging from a bloody civil war, the United States in the late 1860s was still regaining a sense of itself. University rowing was an unlikely source of national attention and – apart from the professional scene – was viewed as the hobby of a few elites at a small handful of Ivy League colleges.

“There had been an early international race in 1867 in Paris,” explains Miller. “A Canadian crew from Saint John, New Brunswick went over and won and were called the ‘Paris Four’.” While Harvard had not attended, they became determined to challenge Oxford or University of Cambridge, whose famous Boat Race, founded in 1829, had inspired the first Harvard and Yale University contest in 1852.

“Oxford narrowly accepted the challenge,” Miller continues, pointing out that the biggest hurdle proved to be equipment. “US colleges were racing coxless sixes, whereas in Britain they raced coxed eights. Oxford insisted on coxed fours, Harvard agreed and they decided to race in London in August 1869.”

[PHOTO src=”140410″ size=”mediumLandscape” align=”right”]

Popular enthusiasm

“This was something very big and very new,” says Miller. “It was the first international university race; it was a challenge that excited public attention in Britain and the United States. Countless inches of print, newspapers and magazines built it up and built it up.”

The trans-Atlantic telegraph cable – the latest marvel of modern technology – allowed for an almost Twitter-like transformation of communications. “Without the telegraph, it would have taken weeks for news to cross the Atlantic by boat,” says Miller. “Now there was daily reporting of what the crews were eating and when they rowed. It really allowed the excitement to happen on the US side of the ocean.”

“On race day, it was minute-by-minute reporting,” he says. “I think it was an American on one of the two steamers following the race that would write reports during the race, put them into steel containers and throw the latest report to a boy hired to row out to the steamer and rush it back to the telegraph to cable it to the US.”

“There were all sorts of events planned in case Harvard won,” continues Miller. “This was right across the United States, not just a local Cambridge, Massachusetts event.” New York planned for fireworks and bonfires were planned as far away as the new states and territories of the Mid-West, areas far removed from any rowing tradition, but swept up nonetheless in the excitement.”

The race

“There was tremendous excitement during the race with a sea of hundreds of thousands of people trying to watch the event,” Miller says. “Some people rode horses and raced from the half-mile mark to the two-mile mark to watch again. The river was locked down and a chain drawn across the Thames at the start to block the river.”

“Even the race was exciting,” he continues. “Oxford had the best crew that Britain had ever put on the water. The British had never expected anything from a small school like Harvard. Harvard were a small crew in a strange boat and the tideway in London is tricky if you don’t know what you are doing.”

For all that, it was a close race. “Harvard led for about the first half,” Miller recounts. “They put a lot into the first half. Then Oxford pulled level and went on to win by a few lengths. One of the Oxford crew, JC Tinney said it was the toughest race he ever had. Harvard and American rowing earned a huge amount of respect.”

Legacy

While Harvard lost the race, the impact of the event is difficult to understate, according to Miller. One major result was a thaw in Anglo-American relations. “The British had supported the South in the Civil War because of their reliance on cotton,” he says. “Relations were very frosty. Political historians have pointed to this event as really breaking the ice.”

“The sportsmanship and competitiveness displayed by both crews helped set a tone,” Miller continues. “They both gave a little bit and they both stuck to their honour.”

The wave of rowing fever surged across the United States. “If you look at the colleges rowing and number of clubs formed in 1870 and 1871, there were dozens of amateur rowing clubs right from New Orleans to Jacksonville.”

In 1871 there was also the establishment of the first intercollegiate rowing association (the Rowing Association of American Colleges) and, Miller points out, “the first national championships of any sport also took place in 1871.”

“The popularity of rowing colleges exploded,” he says. “It was night and day between the numbers of participants. The event probably popularised rowing more than anything else in the US. Even up through 1936 and the ‘Boys in the Boat’ era, I can trace all of that back to this event in 1869.”

Find Miller’s full article here.

A British take on the anniversary by Chris Dodd here.